Doing laundry for citizen research on microplastics

In the IVN Amsterdam newsletter (October 2022), I read that the University of Amsterdam was looking for 100 citizen researchers to participate in a study on microplastics from synthetic textiles. I didn't have to think long and decided to register immediately.

Unawareness

I have always loved fashion and clothing but in recent years I became increasingly aware of the pollution and poor working conditions in the fashion industry and fast fashion. I found out that the fashion industry is even the second most polluting industry. However, the information I had obtained so far was always about the negative effects of the production and disposal phase of clothing. I wasn’t aware of the fact that we also burden the environment when using our clothing. I knew that microplastics end up in the oceans and in our food, but I had no idea that our clothing is a major source of microplastics. Apparently I wasn't the only one. “Research shows that Dutch people are hardly aware of this. 93 percent of all adults does not know how much plastic is in their clothing and the majority underestimates this by almost half," I read in an article by Duurzaam nieuws. One of the UvA researchers also indicates that even colleagues, who are to some extent aware of the research, did not automatically see a connection between their clothing and microplastics. It is clear that more awareness is needed and I wanted to contribute to this by participating in the research.

The problem

To understand exactly what the problem is, I decided to do desk research myself. I wanted to understand what those microplastics in clothing actually are, how they pollute the environment and how polluting they are.

Plastic fibers

Many of the fiber types used for clothing production are plastic fibers (synthetic). According to AEG, about 64% of new clothing today is made of plastic. The best-known plastic fibers are polyester, microfiber, elastane and nylon. They are widely used because they are cheap and because of their functional and comfortable properties. Due to friction during washing, garments lose small fiber particles. According to scientists, particles smaller than five millimeters and larger than 100 nanometers are considered microplastics.

How plastic fibers end up on land and in the oceans

PlanetCare indicates that waste water treatment plants (WWTPs) can capture between 60% and 99% of microfibers, depending on the technology used and other factors. However, in the water cleaning process, a large quantity of sewage sludge is recovered which consists of organic matter. This is where the microfibers also end up. Statistics show that many of developed countries use sewage sludge directly in land applications, as a fertilizer replacement for example. The only country where the sewage sludge is completely incinerated is The Netherlands. In Switzerland, Germany, Austria and Slovenia most of the sewage sludge is incinerated. However, countries such as Portugal, Ireland, UK and Spain use at least 75% of sewage sludge in land applications.

The microfibers that are not captured by WWTPs eventually end up in the oceans. These microplastics are eaten by fish and end up in our food as well. According to the WWF, each person ingests an average of about five grams of microplastics per week through food. This is approximately equal to the weight of a credit card. Last year, researchers from the VU also demonstrated for the first time that microplastics are found in our blood.

Extent of pollution

About 35% of microplastics in oceans come from fibers from synthetic clothing. This makes synthetic clothing the largest source of microplastics. This is followed by car tires (28%), dust particles from urban environments due to wear and tear (24%) and other sources. Two plastic bags of microplastic fibers are released per household per year. Globally, this is approximately half a million tons (500 million kilos) ending up in the oceans, which is equivalent to almost 3 billion polyester shirts.

The research

Until now, little research has been done on the shedding of microplastics when washing synthetic clothing. It is also the first time that citizen research has been conducted on this. According to the UvA this is necessary because it allows a large dataset to be obtained under realistic conditions. The research that has been done so far has only taken place in a lab where small pieces of textile have been examined. This makes the studies less representative and the results are also contradicting.

With this citizen research, the UvA wants to investigate the factors that affect the release of microfibers during the washing of synthetic clothing. These factors include the washing temperature, the type of detergent, the washing time, and the spin speed.

The citizen research I participated in was a pilot study called Meta for which 100 people from the province North-Holland had registered. 75 of the 100 registered actually started the research. From the period November/December 2022 until the end of February, each citizen researcher had to do 10-12 laundries and record the data of each wash.

Doing laundry as a citizen researcher

After registering for the research, I had to pick up a box with the instructions, a special laundry bag from the Guppyfriend brand, a scale, a lint remover and other supplies. With each wash, I had to put 2-3 garments in the Guppyfriend laundry bag. For each wash, I registered the weight of the garments and what fabrics they are made of on Meta's website. I also had to fill in the barcode of my detergent and the washing program. After the wash, I would let the laundry bag dry and the next day I would remove the fibers with the lint remover. Then I had to attach the sheet on a transparent cover that I then photographed. I uploaded these to the website and at the end of the research I sent all the samples by mail to the UvA. After each wash I cleaned the inside of the laundry bag with a vacuum cleaner.

Patience is a virtue

Participating in this research did require some patience! Doing the laundry quickly wasn’t really possible for a few months. There were times when I really didn't feel like going through this extensive step-by-step routine just to do a simple laundry, but I didn’t give up and was eventually able to report 10 loads. Below you can see the sample of my seventh wash.

Image: Sample of micro fibers

Laundry bag and alternatives

The Guppyfriend laundry bag is available to consumers and can be ordered online for approximately 30 euros. Guppyfriend claims that the laundry bag stops more than 90% of microplastics and that fewer fibers break down, meaning your clothes will last longer.

I was very enthusiastic and kept using the laundry bag after the research as well. Unfortunately, I soon discovered that the clothes in the laundry bag cannot be properly centrifuged when the bag is fuller, even if you fill the bag to a maximum of 2/3 according to Guppyfriend's instructions.

Filters

That's why I started doing my own research again to see if there are alternatives. I soon discovered that there are also filters on the market that you can easily install on your washing machine yourself. For example, Planetcare and AEG offer these filters and claim that they stop 90%* of microplastics. This means that 10%, which is equivalent to hundreds of millions of microplastics, does find its way into the land and water, but it is better than nothing, I thought. The AEG filter only fits AEG, Zanussi and Elektrolux washing machines, but the Planetcare filter can be used for all washing machines. Compared to the laundry bag, it is a more expensive alternative; At Planetcare you pay almost 60 euros for 3 filters that each last 20 washes. You can also purchase an XL kit of 13 filters for 145 euros. That is just over 11 euros per filter and therefore a lot cheaper. Dutch people do an average of 2.9 loads of laundry per week. That means you need 7-8 filters per year. Up to 700,000 microfibers are released from one load of laundry. With the XL package from Planetcare you will therefore spend less than 90 euros annually to prevent almost 100 million microplastics per year from ending up in the environment and in our blood.

Final event citizen research

The final event took place on 31 March 2023 to which all citizen researchers were invited. I was of course very curious about the first results of the research and attended the event. During this evening, students from the Earth Sciences and Future Planet studies presented their research proposal.

Microplastic identification

They also showed how the synthetic fibers on the returned lint roll sheets can be identified by a computer program. With the naked eye you can hardly see the fibers on the sheets. This caused some citizen researchers, including myself, to wonder whether that many microplastics are actually released during washing. When we saw a sample (see below) in which the microplastics had been identified by a computer, our doubts were quickly gone. It turned out that a sample sheet contains thousands of microplastics that cannot be seen with the naked eye. This may even be less than when no laundry bag is used because, as Guppyfriend claims, the laundry bag prevents fibers from breaking down more quickly.

First results

The first results based on the 448 submitted samples (washes) show that some fabrics such as acrylic and polyamide cause more microplastics to be released per gram of clothing. The use of fabric softener and the washing temperature could make a difference, but this will be further investigated by a Master's student in the lab. The type of detergent also seems to make a difference.

Since this is still a pilot study, the number of samples are limited and the results are therefore not yet significant. However, the data is a good starting point for further research by the team of students now working at Meta.

Follow-up research

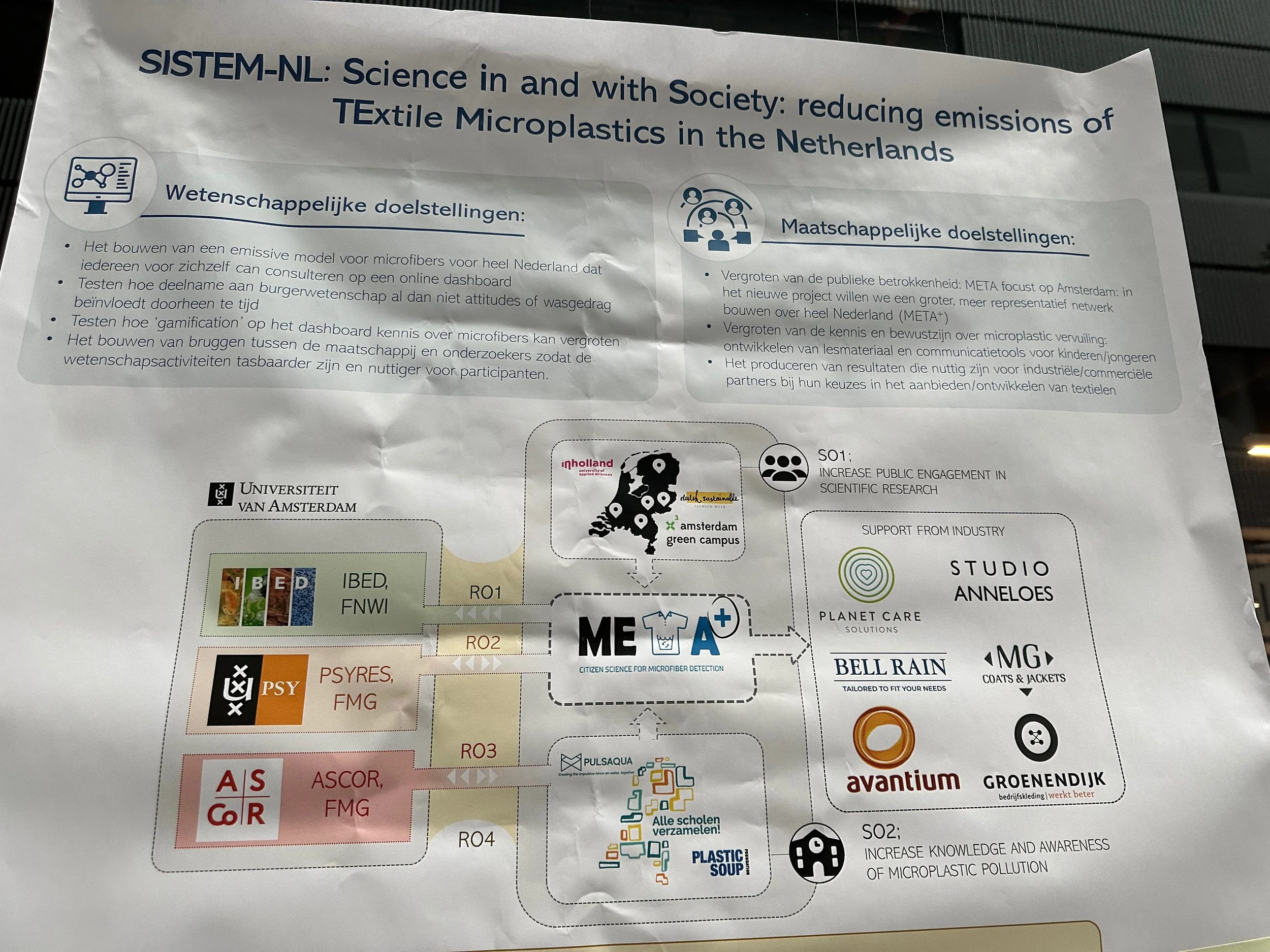

META researchers are currently working to obtain funding for a larger research project called Sistem-NL. At the end of April 2023, the researchers will be informed whether funding will be granted**. The research has various scientific and social objectives. The intention is that in addition to the research with the laundry bag, a citizen research will also be started with filters.

While the research with the laundry bag can map the effect of various factors, the research with the filter will mainly answer questions such as what a household's emissions are over a certain period of time.

We were also asked about possible barriers to participating in the study with the filter. I indicated that it should be easy to install the filter yourself. An advantage of this research for citizen researchers compared to the research with the laundry bag is that it requires much less administration. If you would also like to help with the follow-up research, you can sign up here or keep an eye on Meta's website.

Less synthetic clothing

As Meta was a pilot study, further research is needed to determine which factors influence the release of microplastics during washing, and to what extent. We can of course use a filter or laundry bag to filter the microplastics, but what would be even better, is if we buy less synthetic clothing and more clothing made from (fully) biodegradable materials.

Biodegradable materials

Completely biodegradable materials include linen (made from flax), hemp, wool and cotton. In addition, there are also semi-synthetic materials that partly contain plant-based fibers, such as Lyocell, Viscose and Modal. One of the guests at the closing event who works in the clothing industry noted that natural fibers are also often dyed and chemically processed. If these fibers end up in the water, this can also be harmful to the environment. Fortunately, more and more natural textile paints are coming onto the market. For example, I came across Zeefier during the Floriade, which makes textile dyes from seaweed.

Conclusion

After participating in this research, it has become clear to me that these microplastics have macro consequences. Current solutions may not be perfect, but there are plenty of ways for us as consumers to do our part and prevent millions of microplastics from ending up in nature and our food every year. In addition, it is of course also important that producers take their responsibility. The Plastic Soup Foundation started the Ocean Clean Wash campaign in 2016. The goal is to reduce pollution from synthetic fibers by 80% in the coming years. This is done by putting pressure on clothing manufacturers and washing machine manufacturers and supporting the development of products that prevent fiber run-off. There is a long way to go, but awareness is the first step, so please share it with others!

*Update: PlanetCare is launching the PLANETCARE filter 2.0 in 2024, with a scientifically proven 98% filter retention.

** Funding has been awarded in the meantime.